Hi! Lucy Harley-McKeown here again, bringing you the latest of what’s going on in New Power. Last time we looked at humans fighting to be recognised in a world of machines, and spoke to Unions 21 about why joining a union is a bit like getting married.

This time we wade through the acronyms to look at some tech-focused campaigns born from old unions doing new things.

As always, we love to hear your comments / thoughts / suggestions for coverage, so if a thought strikes you while reading this, please do hit reply or share.

A workplace newsround

In what is usually a pretty quiet month for work, throughout August, the topic of unions and workplaces has enjoyed pretty heavy coverage. The surprise election of Sharon Graham at Unite led to The Economist slugging their piece with ‘bosses beware’, while she pledged to take on Amazon. There was also this thoughtful piece in The Guardian’s comment section by author Eve Livingstone on why it is imperative unions keep up with a changing work landscape.

Elsewhere, the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain won a hard-fought campaign to bring outsourced cleaning and security operations in-house, a move which will improve conditions for a predominantly BAME workforce facing inferior conditions and pay.

There’s also been widespread shortages of select items in supermarkets and in fast food joints due to a shortage of HGV drivers to ferry the goods. There’s been some debate about the merits of raising wages in the midst of speculation about inflation and historically low interest rates.

Meanwhile, there was a whiplash-inducing five-day turnaround by platform OnlyFans on its decision to ban sexually explicit content at a request by its bankers. This would have left scores of creators who had used the app as their main source of income during the pandemic in the lurch. The debacle left many questioning the powers banks and payment services have over marketplaces and by what means people that publish on the platform could hold more power. Some even questioned if it was time for a sex worker co-op. JustFor.Fans has been touted as an alternative.

UTAW: Bringing unions into the tech age

From tech platforms and bankers with too much power, to a new union trying to offer something for a modern workforce, United Tech & Allied Workers (UTAW)’s spokesperson, Mark Storm shares his thoughts on the future of organising.

Founded in 2020 in association with the Communication Workers Union (CWU), UTAW’S mission is simple: to help employees in tech workspaces – from software engineers and startup employees to Amazon warehouse workers. The link-up is an example of old unions and new unions uniting; an attempt to bridge the gap, using the clout and backing of old power with the space and autonomy of new methods.

Over the last 10 years, a new kind of economy has emerged through globalisation enabled by the internet. Born out of new companies and, in turn, employment pathways forged in the wake of the financial crisis, both established tech companies from the US such as Facebook, Google and Amazon and new, spunkier start ups have flooded the market with jobs, money and some dodgy workplace practices.

“In terms of unions, we didn't really see anything in the landscape which was catering to tech workers, who are an example of a new kind of worker,” says Storm, who cites union membership reaching an all-time low in the UK as evidence of a need for new spaces.

According to the latest government statistical bulletin, in 2020, the proportion of UK employees who were trade union members hit a low of 23.3% in 2017. In 2019 that number had risen only slightly to 23.5%. Union membership as a proportion of employees has fallen from 32.4% in 1995.

The rise in trade union numbers among employees was driven by the increase in female members, up 170,000 on the year to 3.69 million in 2019. This was the highest number of female employees who were trade union members since data began in 1995.

So, out of frustration with old, clunky systems and new dodgy practices, UTAW has built a place new workers can come together in.

With this, came the building of its own state of the art infrastructure on the cloud. These new systems, Storm says, had to be safe and secure, and, crucially, not on Google. After all, some members of the union are Alphabet employees.

Membership of UTAW has swelled during lockdowns. Storm says the majority of the membership is made up of young white collar software engineers – a significant portion of whom have never been in a union before.

“I think that speaks to how much the unions have to frankly evolve and adapt. On union training courses the undertone is very manager-worker divide. And as you know, in software, it's not like that anymore. If you work at a startup you might be a worker one day, you might be a manager the next day.”

The organisers created and launched the entire project online, having asked core questions: How do you organise in this space? How do you make sure that information gets across to the workers? And how do you make sure that the workers understand their rights?

Part of the union’s wider mission has been to foster a kind of community that makes it a welcoming place. It has a decentralised organisation online, where people talk about things like bikes and cooking, and have social contact. The meetings are also not conducted that formally. This has echoes of the historic place of unions as a community with social spaces and the working men’s clubs of the past decades.

“We are very informal and people-driven. If people want something they ask, and we try to do our best to do it. We don't drive process,” says Storm.

Storm says that many tech workplaces, particularly startups, simply aren’t aware of some standard employment practices and that much of his work as a rep comes with educating HR representatives and people that run companies as to the correct way to treat people.

UTAW’s current campaign to educate and help workers navigate the ills of employee surveillance was born out of demand from its own workers, and wouldn’t have been possible without the technical expertise the organisation has on hand. Many have an in-depth understanding of coding and what tech can do as well as different functionalities of systems and platforms. The campaign looks at what surveillance is, how it's used, how to combat it and what to do next if you feel your rights have been breached.

“I think you've got to play to your strengths. And if you have a bunch of software engineers and techies, and you've got a crucial topic that's suitable, you can make a difference,” says Storm.

UTAW feels there is scant information out there for people looking for answers independently – and surveillance is an issue that routinely affects many workers in industries other than tech. In many other places, such as media organisations and banks, people are monitored on whether or not they are at their desk, through their billable hours, and through the amount of time they have spent on or offline on messaging platforms such as Slack.

“We've got the Information Commissioner's Office where hardly anybody knows about it. They've got some vague guidance, which is not really actionable. And then you've got very, very, very little enforcement,” says Storm.

Through understanding the techniques CWU uses and linking up their own expertise, UTAW has bridged a crucial generational and skills-based gap.

Tim Martin has left the chat: Wetherspoons and organising on WhatsApp

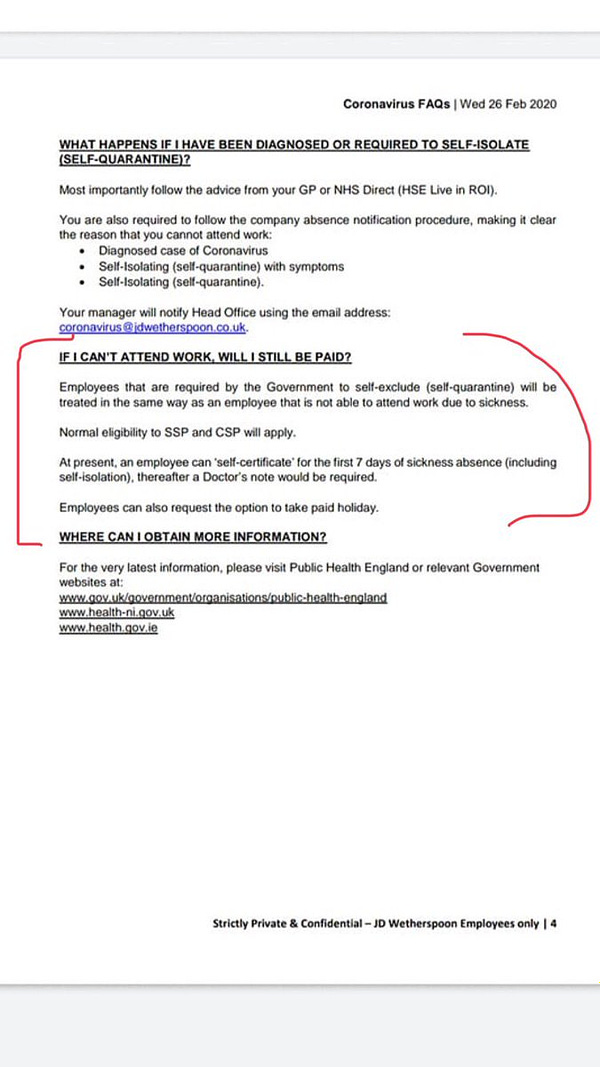

From an almost totally new union, to old unions working together to organise using tech, here’s how workers fought back against the machine of Wetherspoons at the start of the pandemic.

As the UK was catapulted into its first lockdown last year, notorious ‘Spoons boss Tim Martin appeared on video link, pint in hand, to tell his 45,000 workers he wouldn’t be waiting for government support to kick in before sending them home. Martin said he would simply close the pubs and stop paying them.

At the time of the closure, the TUC estimated that nearly two million UK workers were not earning enough to qualify for statutory sick pay, including one in 10 working women. The furlough scheme was still in the works and COVID was not going away.

So the Bakers and Food Allied Workers Union (BFAWU) and the TUC sprang into action. With the reach the BFAWU had in a select number of pubs across the chain the organising began.

In a move that demonstrated quick thinking and agility and following an online form which allowed workers to speak about what was happening, 250 workers were organised into WhatsApp groups which quickly became an important information channel. An organised “Happy hour” each evening – a time slot where people could air their grievances – meant people’s phones were not flooded with messages at all hours of the day. It was a way of seeing what was going on in other pubs and joining the dots online.

“So there was a really fruitful, long-term conversation that was going on there between people who could never normally meet, talking about the challenges of working in that environment,” says John Wood of the TUC.

In writing the organising code for Wetherspoons – a guide which others could follow – and working with other organisers in BFAWU crucial alliances were made with other parts of the industry, and worker voices were heard within the company for what felt like the first time.

“They got people willing to step up and talk about how working at Wetherspoons was affecting them and give some really good personal testimony,” says Wood.

Wood thinks things are slowly changing in unions, with a shift to digital partially having been accelerated due to the pandemic. But at the same time the generational lag on membership and involvement has meant that things are well behind where they would be if unions were built from scratch today.

These stories show two sides to how technology is being used and its potential to transform union organising.

Thanks for reading! See you next time for a look inside GlassDoor.